“I Am Making the World My Confessor” Mary MacLane, the Wild Woman from Butte

In 1902, a woman named Mary MacLane from Butte, Montana, became an international sensation after publishing a scandalous journal at the age of 19. Rereading this often-forgotten debut, Hunter Dukes finds a voice that hungers for worldly experience, brims with bisexual longing, and rages against the injustices of youth.

April 23, 2025

1903 portrait of Mary MacLane — Source.

A century before publishers started marketing novels as “essential sad girl literature” and newspapers ran headlines about the “cult of the literary sad woman”, Mary MacLane confessed all, at the age of nineteen, and became the enfant terrible of American letters, seemingly overnight.1 “This is not a diary. It is a Portrayal. It is my inner life shown in its nakedness. I am trying my utmost to show everything—to reveal every petty vanity and weakness, every phase of feeling, every desire. . . . These are the feelings of miserable, wretched youth.”2

Born in 1881 in Winnipeg, Canada, MacLane moved with her family to Butte, Montana, when she was ten years old. Her father had died two years prior (“he is nothing to me”), and she spent her childhood with her siblings — “they are also nothing to me” — and her mother, Margaret, a woman some biographers identify as “Anglo-Métis”, of mixed British and Indigenous North American ancestry.3 By Mary’s own account, she graduated high school with “very good Latin; good French and Greek; . . . an empty heart that has taken on a certain wooden quality; an excellent strong young woman’s-body; a pitiably starved soul”.4 She was accepted to Stanford and anticipated that her family’s fortune would see to the costs of student life. (Her late father had built a steamship empire, transporting postal freight and commercial goods along Canada’s riverways.) In one version of the story, it was not until Mary was standing on the station platform, awaiting a train to California, that her stepfather admitted to mismanaging a colossal estate. She was curtly informed that there was little to nothing left.5

Studio portrait of Mary MacLane (top) and her siblings James, Dorothy, and John (left), ca. 1900 — Source.

And so, Mary MacLane stayed at home and followed a singular ambition: “I wish to write, write, write!”6 Her first book was drafted when she was just nineteen. Originally titled “I Await the Devil’s Coming”, The Story of Mary MacLane (1902) records four months in the life of its author. Nothing much happens in the outside world beyond study and maintenance: she makes breakfast, cleans the bathroom, tidies her bedroom, reads, and walks. But her inner life is full of action, as she desires, dreams, and rants against the injustices of youth and sex. “I am obscure; I am morbid; I am unhappy; my life is made up of Nothingness; I want everything and I have nothing.”7

MacLane’s voice is effortlessly conversational — a mix of emotional observation, self-celebration, and autofictional anticipation, with no shortage of cruelty — and, a century on, sounds mostly unworn, modern. The narrator defines herself in many ways: as a “thief”, “vagabond”, “liar”, and “a philosopher of my own peripatetic school”. She tirelessly expresses pride in her mind and her “fine young body that is feminine in every fiber” and brims with a desire to experience all aspects of life, except, perhaps, modesty.8 The word “genius” occurs eighty-nine times in this book, the phrase “I am a genius” thirteen times. She extensively (and often unkindly) describes the various ethnic groups living in Butte — Cornish, Jewish, Finnish, and so on — before declaring, wholesale, that “the souls of these people are dumb”. Her disdain for others fills a broad church; she must stand apart, in every way.

I am charmingly original. I am delightfully refreshing. I am startlingly Bohemian. I am quaintly interesting—[all] the while in my sleeve I may be smiling and smiling—and a villain. I can talk to a roomful of dull people and compel their interest, admiration, and astonishment. I do this sometimes for my own amusement. As I have said, I am a rather plain-featured, insignificant-looking genius, but I have a graceful personality. I have a pretty figure. I am well set up. And when I choose to talk in my charmingly original fashion, embellishing my conversation with many quaint lies, I have a certain very noticeable way with me, an “air”.9

Throughout The Story of Mary MacLane, she writes unabashedly about her romantic interest in both women and men, and records at length her fantasies of marrying Napoleon and the Devil in passages of self-immolating lust: “Hurt me, burn me, consume me with hot love, shake me violently, embrace me hard, hard in your strong, steel arms, kiss me with wonderful burning kisses. . . . Treat me cruelly, brutally.”10 Elsewhere, she reflects upon the unparalleled pleasures of love between women in an era when there were few precedents for such explicit divulgences. The book is interleaved with feelings for Fannie Corbin, her former English teacher at Butte High School, whom she calls the anemone lady. “I feel in the anemone lady a strange attraction of sex. There is in me a masculine element that, when I am thinking of her, arises and overshadows all the others”, she confesses. “‘Why am I not a man,’ I say to the sand and barrenness with a certain strained, tense passion, ‘that I might give this wonderful, dear, delicious woman an absolutely perfect love!’”11

The first page of Mary MacLane’s 1901 manuscript of “I Await the Devil’s Coming”. Aside from a few changes to the punctuation, the text is largely the same as its published version — Source.

There may be something quintessentially American in MacLane’s confessional style and public displays of capacious desire, but we can also detect the influence of Marie Bashkirtseff’s journals. (In addition to “The Wild Woman of Butte”, MacLane was known in her lifetime by H. L. Mencken’s sobriquet: “The Butte Bashkirtseff”.)12 For her own part, MacLane did not think the comparison entirely apt. “Bashkirtseff, with her voluptuous body and her attractive personality, is after all a bit ordinary”, she writes in The Story of Mary MacLane.13 “My genius, though not powerful, is rare and deep, and no one has ever had or ever will have a genius like it”.14 She nevertheless acknowledges that Bashkirtseff was a genius, along with Olive Schreiner, Victoria Woodhull, and George Eliot. For male writers, however, she reserves slightly more needling praise:

When you read somewhere that Dr. Johnson is said to never have washed his neck and his ears, and then go and read some of his powerful, original philosophy, you say to yourself, “Yes, I can readily believe that this man never troubled himself to wash his neck and his ears.” I, for my part, having read some of the things he has written, can not reconcile myself to the fact that he ever washed any part of his anatomy. I admire Dr. Johnson—though I wash my own neck occasionally.15

Soon after finishing a draft of The Story of Mary MacLane, she mailed it off, for reasons unknown, to the Fleming H. Revell Company in Chicago, which was originally founded as a publishing house for evangelical literature. Editor George H. Doran later recounted first looking into the manuscript. “I read on into the book — done in the most perfect, painstaking handwriting. I discovered the most astounding and revealing piece of realism I had ever read. Clearly we could not publish it, but Mary must have a publisher.”16 The manuscript subsequently found its way to the editor Lucy Monroe at Herbert S. Stone & Company, who readily accepted and prepared it for publication.

Frontispiece portrait and title page of The Story of Mary MacLane (1902). In the book, MacLane comments on this photograph and reveals its artifice. “My figure is very pretty, to be sure, but not so well developed as it will be in five years—if I live so long. And so I help it out materially with nine cambric handkerchiefs. You can see by my picture that my waist curves gracefully out. Only it is not all flesh—some of it is handkerchief. It amuses me to do this. It is one of my petty vanities” — Source.

The reviews accumulated rapidly. On April 26, The Butte Daily Post ran an article with the title: “Mary MacLane’s Weird, Pagan Book Scorches Butte and Reveals Its Author’s Brilliant, Erratic Genius.”17 Critics were predictably scathing. A New York Times reviewer believed that “no one will take the book seriously or think of putting in a dignified protest against any of its ridiculous rot”, before suggesting that this “girl of nineteen” should be spanked.18 Yet she had defenders — the Washington Post called her debut “the most astounding book that has been brought out in years” — and was not afraid to shoot back.19 “Reporters! Reporters! I hate reporters, and I hate newspapers. They don’t understand me — they don’t go deep enough.”20 The modernist patron Harriet Monroe (sister of Lucy), who would launch Poetry magazine a decade later, published a defense in The Missoulian, reading MacLane’s diaristic entries as blocks of verse. “There are splendid sounds and harmonies in her thrilling, vibratory prose, and to me, the most wonderful thing in her wonderful book is her use of the refrain.” Mark Twain, in turn, bristled at the conceit: “Is the young woman a genie? Or is her book a composite of thoughts that had been written before?”21

In the months after her book’s release, MacLane was in the news constantly, for increasingly bizarre reasons, such as when a fifteen-year-old girl was found dead in Kalamazoo, still clutching her favorite text: “Morbidly mad from the reading of Mary MacLane’s book in the nude, Frances Goodrich put a period to the life that she believed she was tired of.”22 (When asked about her culpability, MacLane demurred: “I am not at all surprised. She lived in Kalamazoo, for one thing, and then she read the book. Who should be blamed, me or Kalamazoo?”)23 A month after that, one Samuel Consentino was arrested after plotting to kidnap MacLane during her “lonely midnight rambles”, while the head of the Butte Public Library tried to ban her from the shelves: “Mary MacLane’s book reeks with abominable passages”, he announced, “it is injurious to the morals of the city.”24 A few months later, the young organizer of Chicago’s Mary MacLane Society stole a horse as memoiristic fodder for a novel-in-progress.25 After her arrest, the horse thief gave an interview worthy of her beau ideal: “Yes, I have read Mary MacLane, but I am a stranger character than that.”26

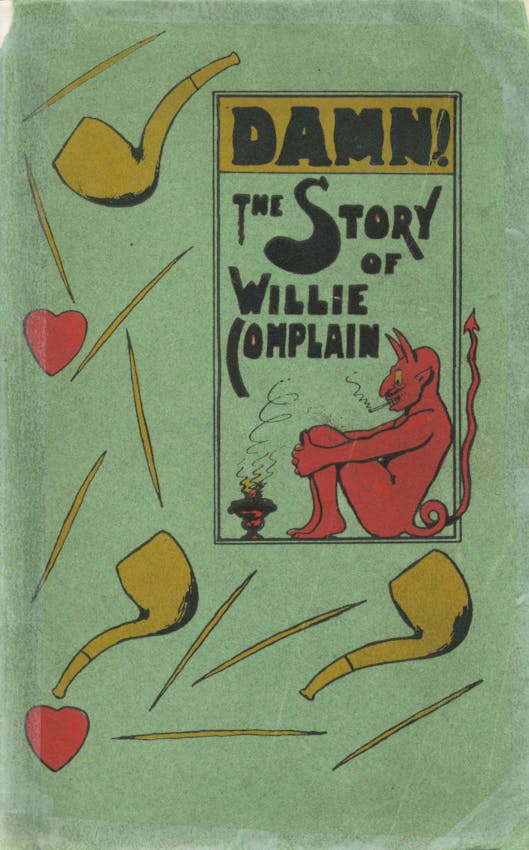

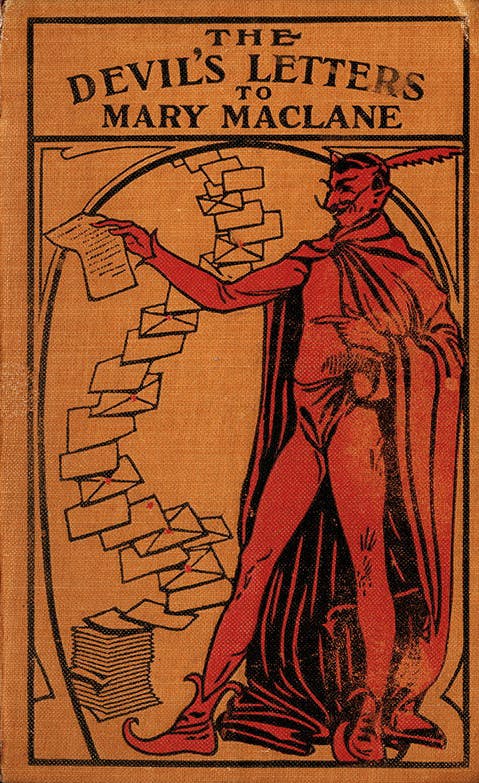

Mary MacLane quickly became a national sensation. She sold almost 100,000 copies in the first month and, by some accounts, made a swift $720,000 in royalties (today’s money here and throughout).27 Mary MacLane societies popped up across the country. She leased her name rights to a Butte cigar company for $18,000; a Buffalo tugboat was christened in her honor; and the author’s favorite cocktail — an obscure drink called the Slanting Annie — sent bartenders and reporters reeling. “Whole City Guessing. Mary MacLane Nominates a New Poison. Bartenders up a Tree. Confess They Don’t Know What a ‘Slanting Annie’ Is.”28 Spoofs of her work sprang up: The Story of Willie Complain (1902) — “Oh, the utter emptiness of everything but me!” — and a burlesque act featuring a thinly veiled “Mary MacPain”.29 Perhaps the weirdest of all is 1903’s Devil’s Letters to Mary MacLane: “That ‘young woman’s body,’ in its exquisite beauty and symmetry of form, shall become the habitation of worms”.30 The Story of Mary MacLane was soon translated into more than thirty languages.

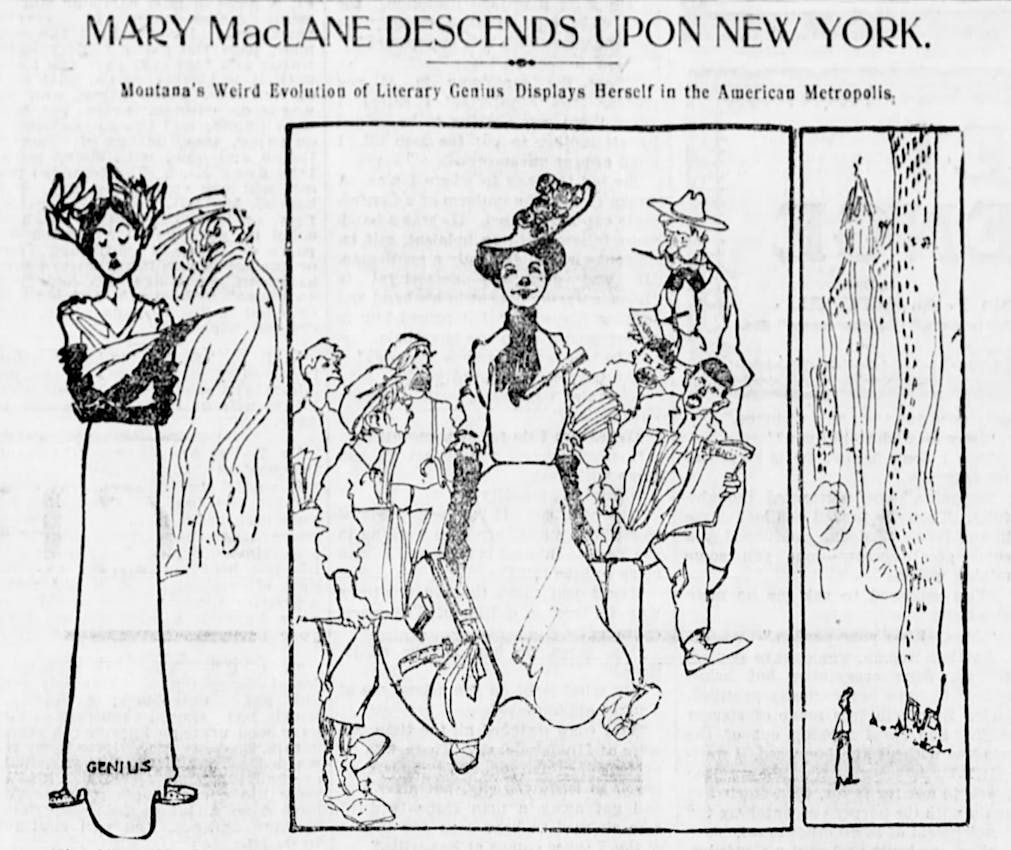

With her fortune regained, MacLane traveled east in the summer. Her first stop was Chicago, where she stayed for a time with Lucy and Harriet Monroe, proposing marriage to the latter sister. “Will you marry me? We will go to Butte and live on liver and bacon.”31 Monroe, in turn, expressed awe to the press: “She is the most powerful personality I ever saw. I never saw such a person with such analytical power as she possesses. Already she knows me better than I know myself.”32 Next stop, Buffalo, where her travels were reported like the procession of a saint — “Beautiful young Genius from Butte will pass through this Town Today” — and then on to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to see Fannie Corbin, whose address reporters doxed.33 Crowds formed outside of the English teacher’s house day and night. The police were occasionally called in to disperse the masses eager for a glimpse of MacLane and her anemone lady. During this period, the novelist and playwright Zona Gale gained the first authorized, in-depth interview with MacLane, in which the twenty-one-year-old appears to distance herself from her younger narrator. “When I wrote my book I wanted to love someone. I wanted to be in love. Now I know that I shall never be in love - and I no longer wish to be. . . . I don't like men. I met a man in Chicago with whom I should like to have been in love, but I couldn't fall in love with him. I was born to be alone, and I always shall be; but now I want to be.”34 Shortly after speaking these words, however, MacLane telegrammed her publisher about Gale: “Beware of Mary MacLane in love.”35 The two went on together to Manhattan, where MacLane accepted a job at Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Portrait of Mary MacLane published in the August 17, 1902, issue of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.“Mary MacLane and Fido Reach Cambridge”, a cartoon published in the July 21, 1902, issue of The Boston Post — Source.

“Mary MacLane Descends Upon New York”, a cartoon published in the August 30, 1902, issue of The Winnipeg Tribune — Source.

In her interview with Zona Gale, MacLane sets out something like a manifesto of performative self-fashioning. “I never give my real self. I have a hundred sides, and I turn first one way and then the other. I am playing a deep game.”36 Likewise, she doesn’t confess herself to the world in The Story of Mary MacLane, but rather “make[s] the world into my confessor”.37 She is always acutely aware of her audience, playing upon their shock and intrigue. Promising truth and transparency, she continually reveals the artifice of her creation — the literary “I”, this “Mary MacLane” — in the same stroke and breath with which she writes and speaks that character into existence across the page. We gradually catch sight of MacLane’s self-serving gambit in this interview: promoting her depth, she is an artisan of the surface par excellence. By nakedly exposing her “inner life”, one that has been baroquely crafted to refract, and even fracture, the social gaze, MacLane pioneered a form of aesthetic insurgency perhaps more familiar to the era of online melancholia than Gilded Age and Edwardian society. “There’s something about caring for an un-self, or self-caring without asserting a self, only an image”, writes the artist and critic Audrey Wollen in relation to “Sad Girl Theory”, her proposal that self-destruction and its “finely honed techniques of display” can act as a form of feminist political resistance.38 Or, in MacLane’s words: “Why shouldn't everybody pose? . . . It is so amusing to pose. Besides, unless you aren’t clever enough to select poses, why ever be yourself to any one? You have a right to yourself for yourself and a few friends. Why should I give myself to you? You are nothing to me.”39 Through tell-all confession, she carves out a space of contumacy.

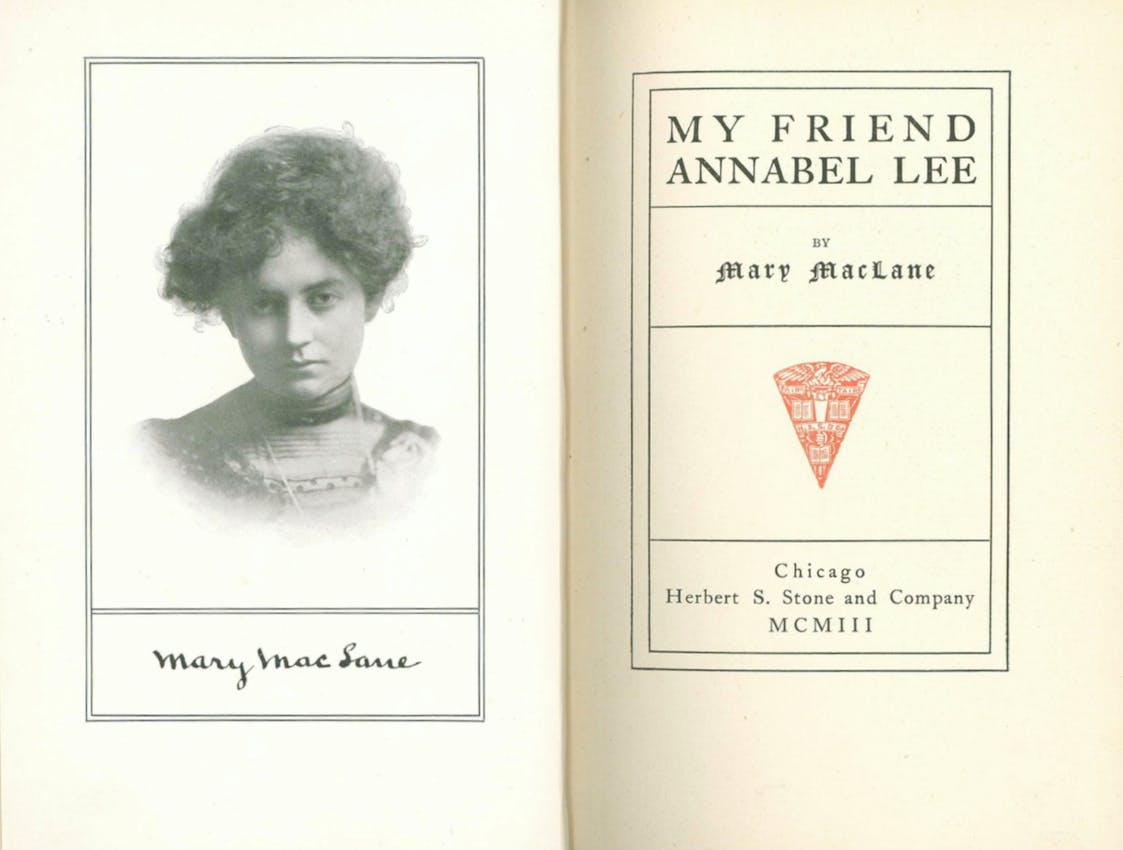

Off the back of the uproar surrounding her debut, MacLane published a second book the following year. Expecting more in the same vein, readers were stumped upon opening My Friend Annabel Lee (1903) — a proto-surrealist account of the narrator’s friendship with a Japanese porcelain doll named after the Edgar Allan Poe poem. Critics, if they spoke at all, often dismissed the effort in a single line. “The book is dull and silly, and apparently written to demonstrate that anything calling itself a book will find buyers.”40 From here, MacLane’s biography gets spotty, a swirl of journalistic gossip, personal silence, and conflicting scholarly accounts. She longed for home, “where people are so much more virile and full of imagination”.41 She cycled through jobs — spells at the Denver Post, Boston American, and New York Evening Journal — and worked, for a time, as a boxing reporter. She squandered her fortune and was arrested for outstanding debts. For many years, she lived with Caroline M. Branson. Forty-four years her senior, Branson was the former long-term partner of Maria Louise Pool, a writer whom MacLane admired. They spent winters in Rockland, Massachusetts, and summered in St. Augustine, Florida, where MacLane loved to gamble: “I nearly always win”.42 She continued to write Monroe adoring letters: “I hope I can see you some day and before errant and wondrous youth has touched us for the last time and fled away.”43 Wherever she traveled, writes Penelope Rosement, “she freely expounded her controversial views on marriage, the family, sex, religion, literature, morality, the idiocy of the rich, and anything else that came to mind.”44

Frontispiece portrait and title page of Mary MacLane’s My Friend Annabel Lee (1903) — Source.

In addition to her articles for newspapers and magazines, MacLane went on to write a final book, I, Mary MacLane: A Diary of Human Days (1917), which was announced five days before the United States entered World War I. Here she returns to her youthful eroticism, writing with even greater transparency about desire (“I am someway the Lesbian woman”) and sexual history: “I have lightly kissed and been kissed by Lesbian lips in a way which filled my throat with a sudden subtle pagan blood-flavored wistfulness, ruinous and contraband: breath of bewildering demoniac winds smothering mine.” Her narrator speaks candidly about the subtle guilt of non-reproductive sex, calling it “the cosmic waste of hot objectless desire”, but ultimately settles in a place of self-affirmation: “there is no vice in my Lesbian vein”.45 In 1918, MacLane capitalized on the silent film era’s fascination with vamps, co-writing and staring in a ninety-minute feature, now believed lost: Men Who Have Made Love to Me. Addressing the audience directly, with no care for the fourth wall, MacLane smokes and recounts her amorous affairs with six male archetypes — The Callow Youth, The Literary Man, The Younger Son, The Prize-Fighter, The Bank Clerk, and The Husband of Another.

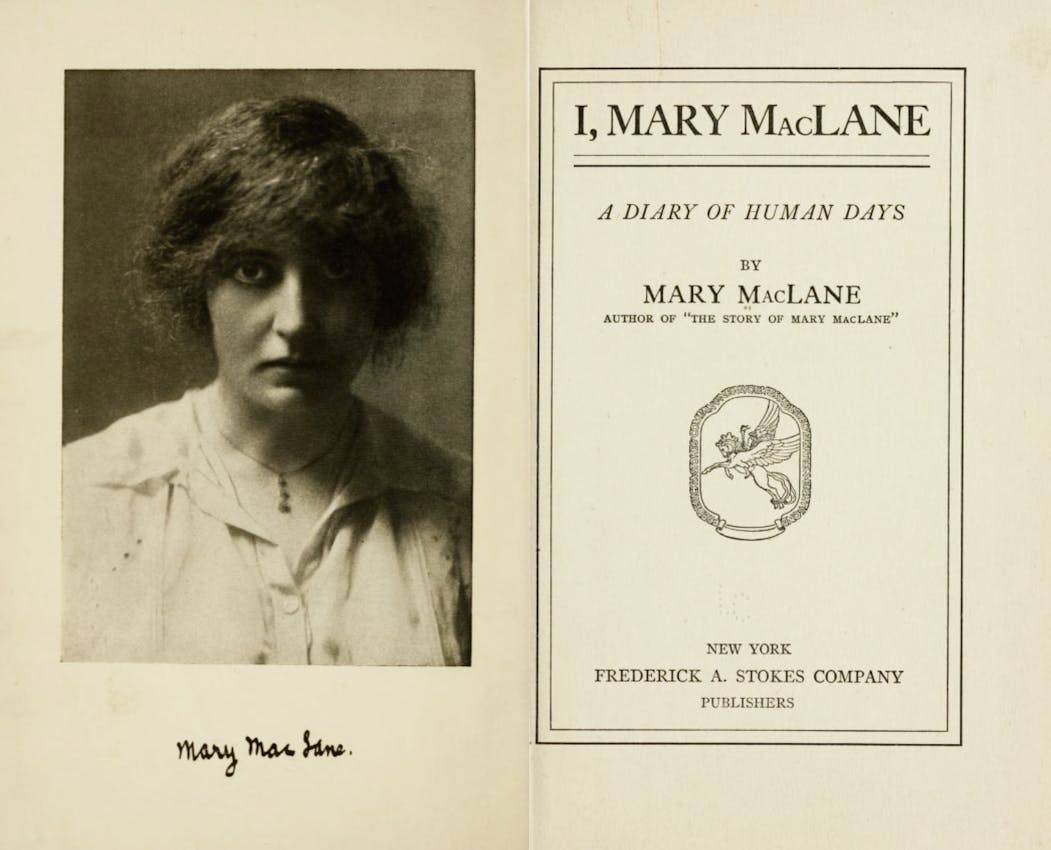

Frontispiece portrait and title page of I, Mary MacLane: A Diary of Human Days (1917) — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Advertisement for Mary MacLane’s film Men Who Have Made Love to Me, from a 1918 issue of The Moving Picture World — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Film still of Mary MacLane from Men Who Have Made Love to Me (1918) — Source.

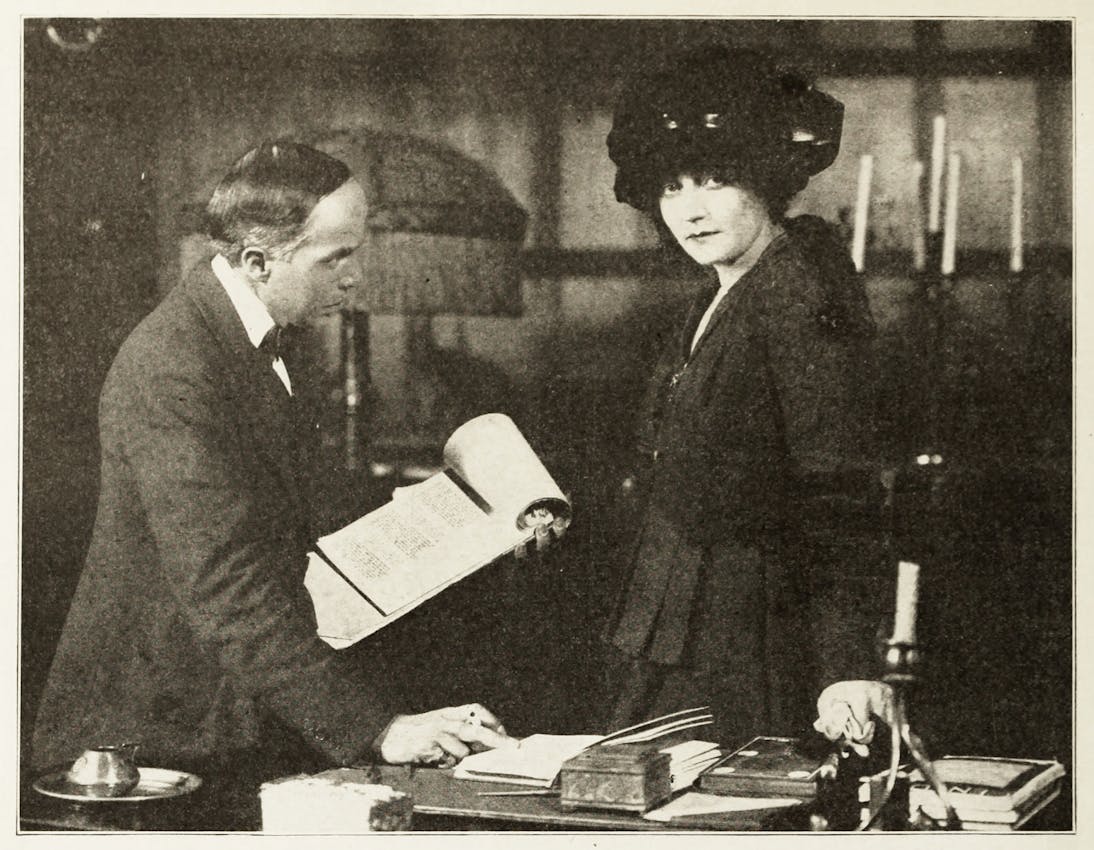

Film still of Mary MacLane with director Arthur Berthelet from Men Who Have Made Love to Me (1918), published as an illustration in “The Movies — and Me”, MacLane’s article for the January 1918 issue of Photoplay — Source.

And then, just over a decade later, in 1929, MacLane’s name splashed across British and American newspapers yet again: the originator of the “modern sex novel” had been found dead at the age of forty-eight, “in a lonely room on the fringe of Chicago’s poorest quarter”.46 She had long been frail — fighting bouts of scarlet fever and tuberculosis — but did not pass away lonely and alone as obituaries luridly proclaimed. In reality, she lived out these last days in the care of her final female companion, a Black photographer named Lucille Williams.47 In one of her last living appearances in the press, as a respondent to a 1925 query in The American Mercury asking if the author of The Story of Mary MacLane was still alive, she wrote: “Yes, I am alive. I live in Chicago and like it. I am fond of the memory of my book of 1902, and any reference to it gives me a little thrill. I don’t quite know what has become of me, but I believe I’ve changed remarkably little since I wrote that bit of revelation. I’m in these times more of a human being than a writer.”48

Once a fixture of tabloids and broadsheets, the Wild Woman of Butte was promptly forgotten after death by the literary establishment. As Rosemont details: MacLane’s books were out of print and difficult to find for decades; she was not included in the three-volume Notable American Women; and later feminist writers failed to claim her as an influence.49 Without biographical justification, excerpts from The Story of Mary MacLane have found a second life in books and academic papers about mental illness — psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist, writing in the London Review of Books in 1995, describes MacLane only as “a schizophrenic patient” after quoting her words.50 But perhaps all this is changing. In 2012, Australian actress Bojana Novakovic wrote and acted in a stage adaption of The Story of Mary MacLane. In 2013, MacLane’s first novel was republished by Melville House with its original title. In 2025, the first book-length biography of MacLane entered the world. Yet still her influence has not been fully excavated. “Always I wonder, when I die will there be anyone to remember me with love?”51

Hunter Dukes is managing editor of The Public Domain Review and Cabinet.

0-edit.jpg?fit=max&w=1200&h=850&auto=format,compress)