Richard Spruce and the Trials of Victorian Bryology

Obsessed with the smallest and seemingly least exciting of plants — mosses and liverworts — the 19th-century botanist Richard Spruce never achieved the fame of his more popularist contemporaries. Elaine Ayers explores the work of this unsung hero of Victorian plant science and how his complexities echoed the very subject of his study.

October 14, 2015

Plate 82 from Ernst Haeckel’s Kunstformen der Natur (1904), in which are depicted a selection of liverworts — Source.

Lying prostrate in his bed in Yorkshire in 1869 just five years after returning from an expedition through South America, Richard Spruce — one of Victorian England’s top botanists, collectors, and explorers — found himself contemplating his gradual transformation into the object of his fervent study: moss. “One day last week a dentist relieved me of four teeth”, Spruce joked to a friend, “and I now belong to the genus Gymnostomum; but by the time you come over I hope to have developed a complete double peristome”. As his health declined dramatically in the following years, Spruce retreated into his beloved collections, spending what little energy he had left by working for just a few minutes at a time on classifying microscopic specimens into meticulous arrangements of sporophytes and peristomes.

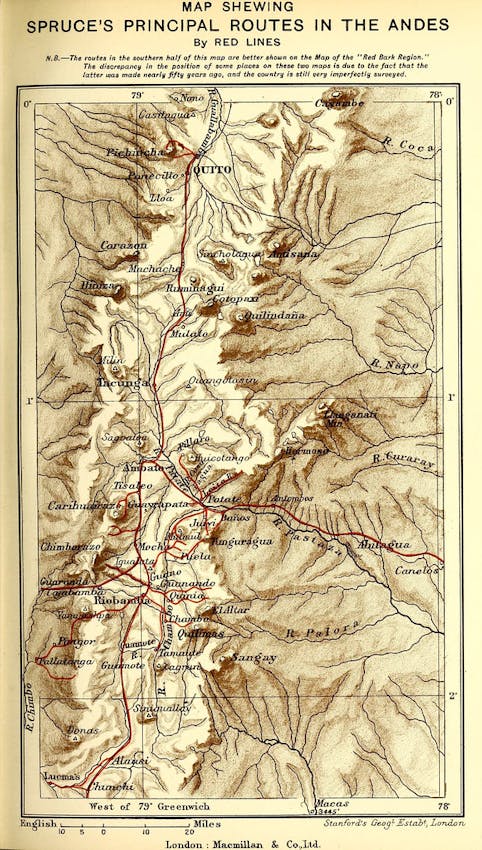

From 1849 to 1864, the botanist trekked along the Amazon and its tributaries, ending up in the Andes of Peru and Ecuador on a successful collecting mission for Kew Gardens and the English East India Company. Today, Spruce is mostly remembered for this final leg of his expedition — under the orders of the famous Sir Clements Markham, he studied, cultivated, and eventually smuggled out young cinchona trees to plant in India as potential treatment for malaria. This swashbuckling story of botanical espionage, though, obscures what Spruce spent most of his life obsessed with: those most minute and mundane specimens of the plant world — bryophytes, or mosses and liverworts. Although bryophytes actually thrive in cooler environments (like England), Spruce’s livelong mysterious bodily afflictions prevented him from living comfortably in these same conditions. Years of inexplicably coughing up blood and suffering from debilitating headaches forced the botanist to conduct his work in warmer, more tropical climes. This, then, is the story of how one of Britain’s most promising, skilled explorers struggled to find a place in Victorian science, unable to shake his love for the underdogs of the plant world.

Map showing Spruce’s route through the Andes from Notes of a Botanist on the Amazon and Andes (1908), edited by Alfred Russel Wallace — Source.

Born in Yorkshire in 1817, the tall, thin, and handsome Richard Spruce had always been drawn to nature’s most unassuming plants. After building unparalleled botanical collection and classification skills in England’s countryside and then in the Pyrenees, Spruce joined his good friends Alfred Russel Wallace and Henry Walter Bates in Brazil at the age of thirty-two, backed and brokered by prominent botanists at Kew Gardens. Reflecting on his Amazonian collections, Spruce described his unusual, and perhaps debilitating, draw to hepatics (liverworts), in particular. “I like to look on plants as sentient beings,” he wrote,

which live and enjoy their lives — which beautify the earth during life, and after death may adorn my herbarium. . . It is true that the Hepaticae have hardly as yet yielded any substance to man capable of stupefying him, or of forcing his stomach to empty its contents, nor are they good for food; but if man cannot torture them to his uses or abuse, they are infinitely useful where God has placed them, as I hope to live to show; and they are, at the least, useful to, and beautiful in, themselves — surely the primary motive for every individual existence.

Indeed, despite his later reputation as a smuggler of cinchona, Spruce had little personal interest in utilitarian plants. Nor was the botanist particularly interested in the tropical species that we usually associate with floral beauty — orchids, palms, birds of paradise, and the like, that made other naturalists famous. Dismissing the picturesque image of the Amazon filled with “gay flowers, butterflies, and birds”, Spruce argued that popular naturalists (like Wallace and Bates) would “utterly mislead” readers, “if they were thereby led to suppose that even a tithe of those beautiful objects were ever to be seen all together, or in the space of a single day”. The beauty of the Amazon, to Spruce, lay in the humble, Godly mosses and hepatics that hearkened back to his botanical ramblings back in Europe, providing respite from the rainforest’s apparently underwhelming — albeit dangerous — daily existence. In a passage scrawled in his journal, and later reprinted in nearly all of his obituaries because it seemed so inherently characteristic, Spruce revealed his innermost botanical leanings. After years of trekking through thick forests, dealing with overturned canoes and lost collections, outwitting a mutinous attack by his native porters, and, as always, dealing with unceasing illnesses, infections, and his usual bloody cough, the botanist “found reason to thank heaven which had enabled me to forget for the moment all my troubles in the contemplation of a simple moss”.

Portrait of Spruce featured as the frontispiece of Notes of a Botanist on the Amazon and Andes (1908), edited by Alfred Russel Wallace — Source.

Mosses and hepatics, in the nineteenth century as now, were — perhaps unsurprisingly — relatively unpopular plants. Lacking roots, flowers, and seeds, bryophytes require tedious, trained microscopic observation in order to study their intricate characteristics. Examining them in the field involves crawling around on hand and knee, dissecting complicated colonies growing on rocks and stumps with a hand lens and tiny forceps. While preserving bryophytes is relatively easy — usually only a single cell thick, they can be dried and pressed even in the dampest and most inhospitable environments — bryological collections seem divorced from any verdant aesthetics usually associated with flora. Piled up herbarium sheets appear uniformly brown and amorphous, their hidden natural beauty only revealed under more careful, time-consuming microscopic study. The sets of mosses and hepatics that Spruce collected in South America (which, when sold to subscribers back in Europe, supplied most of his meager income while travelling) only appealed to serious plant scientists with bryological interests. Rather than providing any insight into the Amazon’s vast biological diversity or potential imperial economic holdings, Spruce’s bryological collections spoke to very specific, disciplinarily bounded discussions about plant reproduction and speciation.

Bryophytes mattered to mid-nineteenth century botanists primarily because of their role as primeval beings, plants that predated almost all other vegetative life amidst a growing scientific fever for evolutionary studies. Spruce’s most popular, oft-quoted journal entry described his realization of the “idea of a primeval forest” upon reaching Brazil, a rich depiction of “enormous trees” that were “decked with fantastic parasites, and hung over with lianas, which varied in thickness from slender threads to python-like masses . . . now round, now flattened, now knotted, and now twisted with the regularity of a cable”. Writing to the director of Kew, William Jackson Hooker, from Ambato in 1858, Spruce appealed to this sense of evolutionary interest while sending back a beautifully complete set of moss specimens. Although he had suffered a period of particularly bad health while travelling through a damp and cold region, the botanist came across a scene rich in bryophytes, delighting him to no end. After listing all of the mosses and hepatics that could be found growing in “shady rivulets”, Spruce wrote that “I had never seen anything which so astonished me”. Taken by the botanical riches, he went on that “I could almost fancy myself in some primeval forest of Calamites, and if some giant Saurian had appeared, crushing its way among the succulent stems, my surprise could hardly have been increased”. The mosses and hepatics that he collected in this “primeval” area brought him a large sum of money, one of the most valuable collections of his fifteen-year expedition.

Illustration of the moss Bryum Glaucum, from Plantarum indigenarum et exoticarum icones (1788) — Source.

Illustration of th moss Hypnum Aquaticum, from Plantarum indigenarum et exoticarum icones (1788) — Source.

Beyond their small role in Victorian botany in an evolutionary sense, bryophytes had a way of working themselves into art and literature as signifiers of privacy and secrecy. Pushing against its scientific reputation as downright boring, moss in particular served to create some botanical, aesthetic sense of a setting that allowed for illicit sexual encounters and for primal yearnings. The reasons for this strange dual identity of bryophytes as both mundane and as primal are relatively clear: realistically, moss provided a soft bed for sexual romps that had to take place outside of stuffy Victorian homes. Serving, perhaps predictably, as a slang term for pubic hair, moss was understood to be consistently moist and jewel-like, glittering like emerald colonies under light. One need only look to the climax of Elizabeth Gilbert’s recent historical novel, The Signature of All Things — a long-coming sexual awakening that takes place in a hidden moss-covered grotto in Tahiti — as evidence for the strength and longevity of this Victorian plot device. Although tropes of sexual encounters occurring in gardens and forests far predated the nineteenth century, both realistically and literarily, these hidden moss grottoes conjured up an image of something semi-religious, some secret refuge from the trials of urban — and overwhelming imperial tropical — life.

Despite eschewing the topic of sex altogether in his Amazonian journals and letters, Spruce wrote excitedly about coming upon one of these hidden grottoes in 1855, just off of the Rio Taruma. After climbing for hours on end to reach a picturesque waterfall, Spruce snuck behind the fall into a space that he remembered as an overwhelming high point of his expedition. Finding naturally produced steps embedded in the cliff, it was:

thus easy to walk under the cataract without being wetted, though the rocks drip here and there and are everywhere thickly clad with ferns and Hepaticae, but especially with Selaginellae, of which I gathered four species not found in adjacent forests. The water falls into a deep trough, from which spray dashed out and is borne downward by the rush of the cataract. The water winds away among mossy blocks and then is lost beneath them for a considerable distance . . . The whole aspect of this mossy cirque, with its broad riband of falling water, embosomed in dense luxuriant forest, in which was visible no palm, was something of an admixture of tropical scenery with that of temperate climes.

Spruce’s reaction to this mossy grotto was nothing short of sublime. Never one to exaggerate the beauty of the tropics, the botanist (whose health was on a brief upswing in 1855) had a private, almost religious reaction to this bryological setting. This day in the “mossy cirque” was one that Spruce seemed unable to forget even after returning to England’s more “temperate climes”.

Plate 72 from Ernst Haeckel’s Kunstformen der Natur (1904), depicting a grove of mosses (referred to by Haeckel as “Muscinae”, a label now obsolete) — Source.

Back in Yorkshire after his fifteen years in South America, Spruce’s health continued to decline. Although he dedicated most of his time to compiling and writing his bryological masterpiece, Hepaticae of the Amazon and Andes of Peru and Ecuador (published in 1885), a more than five hundred page list of all the region’s liverworts and their characteristics, the botanist suffered increasing attacks of intense bodily pains and even routine paralytic seizures. The saddest irony, perhaps, is that Spruce’s illness rendered it incredibly difficult to work with the bryological specimens that he had spent his life accumulating. Writing to a colleague in 1889, Spruce lamented that unbearable headaches prevented him from using the microscope for more than a few minutes at a time. His collections of thousands of mosses and hepatics remained unclassifiable except in brief spells of good health, and Spruce was forced to rely heavily on other bryologists to examine the peristomes and sporophytes necessary for serious study.

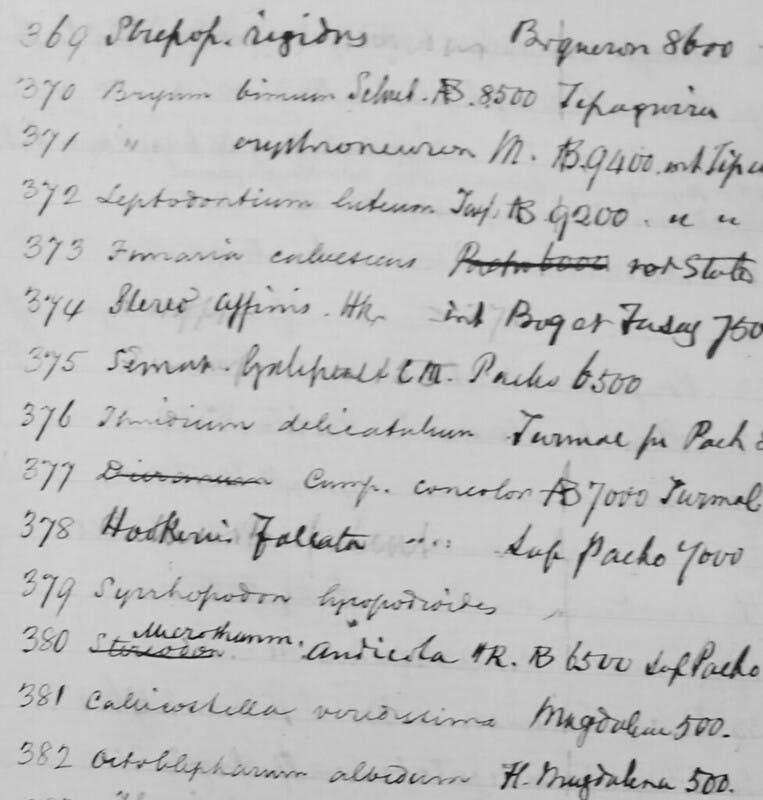

Although Spruce lived to be seventy-six — a remarkably old age for such a diseased and decrepit man in the 1800s — he never wrote the travel narrative of his time in the Amazon that could have secured his fame and fortune. At the time of his death, the botanist had accumulated a massive bryological herbarium, thousands of pages of specimen lists that tracked floral biogeographical distribution, travel journals that described his daily habits in the Amazon and Andes, and countless letters to Europe’s and America’s foremost scientists. His early notes were, and are, considered nearly flawless examples of botanical record keeping. Spruce’s handwriting was impeccable; precise locations, dates, and environmental conditions marked every specimen he collected. His descriptions of mosses and liverworts continue to be some of the most specific and accurate ever recorded. Botanists, even now, regard Richard Spruce as a true “botanist’s botanist”. Hepaticae of the Amazon and Andes remains a usable and useful guide to South American liverworts, and Spruce’s herbarium sheets are some of the most carefully arranged and beautiful specimens of mosses ever created. So why, then, is the naturalist missing from most histories of Victorian science?

The answer, it seems, lies in Spruce’s unceasing love for the meticulous and the mundane. Although these qualities made him a respectable, credible source to his colleagues in the mid-nineteenth century — Spruce, for example, was never accused of exaggerating the geographical range of his expedition, unlike most explorers — everyone seemed to recognize that his work just wasn’t interesting to the general public. His good friend Alfred Russel Wallace certainly tried to popularize Spruce’s work, compiling his journals and letters into the two massive Notes of a Botanist volumes, published by Macmillan in 1908. Indeed, although Wallace believed that the volumes would “take their place among the most interesting and instructive books of travel of the nineteenth century”, he was careful to print the longer, more detailed botanical passages (mostly bryological in nature) “in smaller type, so that they may be readily skipped by those who are chiefly interested in the actual narrative of Spruce’s travels”. Rather, in introducing the volumes to readers, Wallace emphasized the smallest sections of Spruce’s work — his quick and conventional references to the Amazon’s more sensational stories, ranging from naked warrior women to gold and vampire bats. Spruce’s long, detailed, and almost obsessive passages about mosses and hepatics shrank into the shadows.

Richard Spruce, along with his favorite bryological specimens, occupied tenuous, almost dual identities in Victorian science. Both the botanist and his bryological colleagues struggled with how “popular” their work could aspire to be. Although he generally fits into the category of masculine, sensationalist Victorian explorer (along with Wallace and Bates), Spruce was far from the strong, resilient model of conqueror of nature; for most of his life, the naturalist was too sick to work, and spent his favorite days in the Amazon sitting quietly on the ground, examining the miniscule plants that reminded him of home. These miniscule plants, too, fit uneasily into broader botanical categories. While they represented something clandestine, sexual, and primeval in literature, bryophytes were considered relatively uninteresting and even unimportant in a rapidly expanding British botanical empire. Although he never fully transformed into a species of moss, Richard Spruce’s uncommon affinity with the plants relegated his work to the depths of the botanically obscure, wildly useful to other bryologists, but unread and uninteresting to the broader public.

Elaine Ayers is a PhD candidate in Princeton University's Program in the History of Science. She works on natural history, aesthetics, and gender in the Victorian tropics.